When I was 16, I spent part of my summer working at a seafood restaurant in the North Carolina mountains bussing tables. The restaurant was always busy and I had to work my ass off to keep up. I seem to recall that I made about $2.00/hour for that work. I hadn’t yet learned about the North Carolina Wage & Hour Act, and I don’t suppose it would have done me much good if I had.

That same summer I had almost contemporaneously discovered Led Zeppelin and decided that I wanted to learn how to play the guitar. I had an insatiable appetite for live music, and I tried to take advantage of every opportunity to see music performed.

Led Zep sits down for an acoustic set circa 1977.

The North Carolina mountains, like much of southern Virginia, have long been home to many superb musicians that, with almost autistic brilliance, play a variety of traditional and old-time bluegrass, blues, and gospel music. It is rare to find someone who can read music or who knows what an appoggiatura is, but it is common to come across people who you would never suspect as a musician but who can hear a melody and instantly recognize the key of the song and, while playing it, transpose it into three different keys while drawing on a cigarette and telling you out of the free corner of their mouth about the first time they heard the melody, which might have been 30 years prior.

I recall from that summer in the mountains that on any given Saturday night you could (and probably still can) find a few small jamboree halls consisting of one-room buildings that were pretty much in the middle of nowhere and which were packed with people who took turns playing music and dancing. There would be one person on guitar, one on fiddle, one on stand-up bass, and usually one on clawhammer banjo. There was never a pre-arranged set list; there was never a rehearsal. They played whatever they all knew how to play in common, and although a song might be repeated throughout the night, it was never played the same way twice.

After a musician had taken a turn on stage, he or she joined the others who often sat and clapped or joined in dancing that looked to me a lot like square dancing, but I’m not sure if there was any real formality or structure to it.

|

| Warming up on the claw-hammer banjo. |

These gatherings took place nearly every Saturday and word got around. And there was no alcohol served, nor were there any concessions. Everybody that was there was there to play or hear music, and it was euphoric and extraordinary. There were usually no advertisements posted for these events, and there didn’t really need to be. Some of the best musicians in the entire area came to play and listen to music.

I attended several of these old-time music jamborees and learned to love the type of music I heard there. One name I frequently heard mentioned by the musicians was Doc Watson. It was common to hear, “This is an ol’ tune that Doc plays,” or “I can’t pick this like Doc Watson can, but we’ll try to play it anyway.” Doc was a legend among mountain musicians.

One Friday afternoon about 5:00 p.m. a large entourage came into the restaurant where I was working, and we had to put about six tables together to accommodate all of them. The people who made up the entourage walked in slowly, and they seemed to maintain an unusual reverence for one member of their group who was slowly coming up the rear.

The object of the reverence, it occurred to me, was blind, although he wore no sunglasses and he did not have a cane. He held onto the arm of the man walking next to him and stooped slightly at the waist as he walked carefully along. He was brought to the center of the large table that had been assembled for the group, and it seemed that not a syllable was uttered until the blind man found his seat. The manner in which the other members of the party seemed to pay silent veneration to the blind man moved me to great curiosity.

The object of the reverence, it occurred to me, was blind, although he wore no sunglasses and he did not have a cane. He held onto the arm of the man walking next to him and stooped slightly at the waist as he walked carefully along. He was brought to the center of the large table that had been assembled for the group, and it seemed that not a syllable was uttered until the blind man found his seat. The manner in which the other members of the party seemed to pay silent veneration to the blind man moved me to great curiosity.

The restaurant was busy as usual that afternoon, and I recall working myself into significant perspiration as I cleaned the tables in my area. After some time, the blind man and his entourage arose and left the restaurant in much the same unceremonious manner as they came in.

Several minutes later, the man who led the blind man into and out of the restaurant came back in and approached me. He said, “Doc wanted you to have this,” and he handed me a five-dollar bill. As I stood there somewhat amazed, he said, “Doc says hard work pays off.” I was pleased to get the tip, but it didn't dawn on me that the "Doc" the man referred to was Doc Watson until one of the other restaurant employees pointed it out to me.

The five dollars I received from Doc was the only tip I received during my brief career as busboy in the North Carolina mountains. I put it toward the purchase of my first guitar.

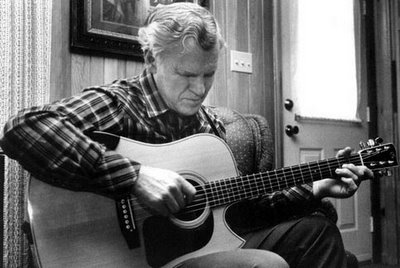

|

| Doc playing a D-minor on his cutaway. |

Last Saturday night, I had the good fortune to be invited to see Doc perform at the authentic and rustic Neighborhood Theatre on 36th Street in Charlotte. Doc played with his grandson Richard (Merle Watson’s son) and Jack Lawrence, the legendary flatpicker. I had seen Doc play previously on several occasions, but it had been at least 10 years since I had seen him play and even longer since I had seen him in an intimate venue like the Neighbhorhood Theatre.

Doc came out in a plaid long-sleeve shirt and black jeans into which a crease had been neatly ironed down the front of each leg. He wore short leather boots that looked like the same kind Elvis wore in his 1968 comeback television special and they appeared to be new or neatly polished (I suspect the latter).

Doc's hair was white like star light and his eyes were black shadows cast by the overhead stage lights onto his brow, which protruded in concentration. His countenance—avuncular but adumbrated, darkling, and mysterious in the glare of the lights—appeared to me similar to what I imagined syphilitic Paganini must have looked like when he took the stage to awed crowds convinced of his partnership with the devil.

Once he found his seat, Doc told the crowd of about 700 that he intended to be as informal on stage as he was in his living room. There was no hint of pretension in the man whatsoever. As he tuned his guitar and became familiar with the position of his microphone, Doc told several endearing stories about his wife and grandchildren that made everybody laugh. He and Richard then played about three or four old-time bluegrass pieces and a couple of blues tunes that allowed Richard to bend some strings and pick some lead blues notes out of the pentatonic major scale at the 5th fret and again at the 12th. Meanwhile, Doc sang the blues.

In the 30-odd recorded blues songs that legendary blues musician Robert Johnson left behind before his untimely death (some say he was poisoned), you can hear something beyond music in his voice; something not just plaintive and not just melancholy. There is blues in the man's voice; blues, like a lost and lonely dog. Blues like hunger, and blues like death. Blues, as if all the pain in the world poured out of his mouth like blood from a cut, like the sound of Christ's breath as he walked with the cross.

Now, maybe Doc can't quite sing the blues like Robert Johnson did in those 30 or so recordings, but it's damn near. How Doc found the blues, I don't know. But the man can sing the blues. It's more than just musical styling. Perhaps it comes from decades of living in the dark with only a child's visual impression of the world (Doc lost his sight when he was just a boy). Perhaps it's just in his heart.

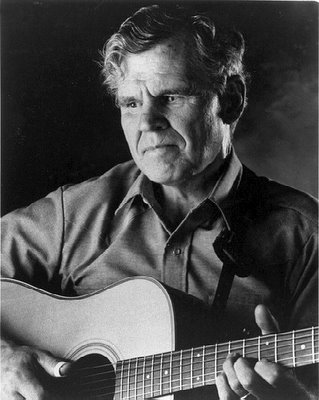

|

| An early picture of Doc Watson with his guitar. |

When Jack Lawrence came out and replaced Richard at accompanying guitar, the pace of the show changed and Doc and Jack tore into several bluegrass standards that require guitar-picking ability almost beyond comprehension. It was not prearranged between Doc and Jack who would play the lead parts and in what sequence. This critical issue was determined by a nod of Doc's head: when he wanted Jack to take a lead, Doc would merely lean back a little and nod in Jack's direction, at which time Jack would sit up so his guitar would be closer to the lead mic, and he'd tear into a dizzying impromptu solo that I doubt Jack or anyone else could ever repeat note for note.

The next time an opening for a lead came around, Doc would announce, "Let me try this one time," or "I'll take this one." Doc's lead parts took on a somewhat different character from Jack's. The notes were probably picked out of the same scales, but Doc's leads were just somehow more musical. Each time Doc finished up his solo and resumed his haunting vocals, every person sitting in front of me would just shake their heads in unison. I heard one fella summarize our collective awe by simply saying, "Son of a bitch."

Every time I see Doc play, I become internally divided because I can't decide whether I should go home and do nothing but practice or just give up the guitar entirely. Plainly, with musicians like Doc out there, I and other guitar players have very little to add.

Doc flatpicked some pieces and played other pieces with a thumb pick, and he played several pieces with a capo, which he called a "cheater." When a song called for a capo on the second fret, Doc would take out his "cheater" and say, "Boys, this one is in the key of two." When he wasn't using his cheater, he would take it off his guitar and put it into his pocket. I assume this was a habit he'd developed over time to ensure that he could find it again when he was ready for it. And when Doc would switch from flatpicking to the thumb pick, he'd wet his thumb by putting about half of it in his mouth before sliding the thumb pick on there.

In between pieces, Doc and Jack were informal as Doc had promised. They would ask one another what song the other wanted to play, and sometimes they'd ask if the other knew such and such a song, etc. Doc would say, "Jack, do you remember that song that Bill Monroe . . . ." It was like watching Delacroix prepare a canvass; it left you with the feeling that you were witnessing something wholly new, something so extraordinary yet empheral such that its essence could never truly be captured and would never appear in precisely the same way again.

Jack started a couple songs that Doc professed not to know, but by the middle of the second bar of these songs, Doc was chording along and adding 32nd-note fills that were faster than imagination.

I found it entirely remarkable not that Doc could play the guitar so well despite his blindness. What is remarkable is Doc's musical ability irrespective of the fact that he can't see. Even viewed next to the playing of Jack Lawrence, a highly acclaimed guitarist and certainly one of the most accomplished guitar players alive, Doc's guitar work has a musical quality in the playing that in all my life and in all of music I have only heard on the rarest of occasions.

There is nothing magical in Doc's technique necessarily, and there is certainly nothing mysterious about the notes he plays -- for most good guitar players who work at it could play the notes and runs Doc plays. It is the music that resides within Doc's heart and soul that sets him apart from other musicians. His music cannot be fabricated and its sincerity cannot be forged, no matter if the notes and rhythms are studied and learned with forensic determination.

Doc's playing has an inescapable musical aspect that pervades every sound he generates, that transcends mere mechanical technique, that breathes profound melodic life into each note, each chord, each run, each soulful syllable that could be reverse engineered to reveal 200 years of mountain-music history and perhaps a thousand years of world-music history and all of which somehow coalesce into pure, perfect music.

I realized several times throughout the show that I was grinning like a mad man. When I looked around at the people next to me and behind me, they were all smiling, too. And I don't doubt the guitar players in the group were trying to decide whether to go home and practice or just give up the guitar entirely.

At the end of the show and with a standing ovation and cat calls from all around, Doc stood up, smiled and nodded to the crowd he could hear but could not see, and without a hint of pretension, he took hold of Jack's arm and walked slightly hunched through the curtain and off the stage, just as he had come into the restaurant where I worked nearly 20 years before.

* * *

(c) Edward K. Hornbeck and John Frum's Galactic Gazette, LLCNote: Copyright information for the pictures contained herein was diligently pursued, but was not located. It appears that these photographs of Doc, much like the mountain music that he plays, have been treated as if they simply belonged to everyone. If anyone owns any of these images, please send me an e-mail at e.k.hornbeck@gmail.com.